5 ESG Policy Trends Changing Business: Now What?

January 26, 2022

Until today, Environmental, Social, & Governance (ESG) has been defined mostly by voluntary practices, as the key policymakers (market authorities as well as national and international regulators) adopted a “sit and stare” approach and let the markets decide how to deal with ESG.

The tide has turned, with jurisdictions now racing to introduce strict mandatory requirements that bind companies to contribute to the public policy goals governments are setting in relation to climate specifically and ESG more broadly.

What’s Changed?

These developments have deep implications for companies, investors, and financial markets. Let’s look at five main policy trends that are significantly reshaping business:

1. No more ESG standards alphabet soup – While new niche frameworks and guidelines will always pop up (let’s keep in mind that ESG evolves constantly), the European Union (EU) mandatory Sustainability Reporting Standards, and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) are de facto the standards every company will have to look at.

This type of consolidation is important, but it’s not the end game. Companies need to take ownership of the issues on which they will act and have a credible process to justify why and how the relevant standards – and there will continue to a variety of relevant ones to use – facilitate accounting and reporting.

2. The era of ESG taxonomies has begun – With mandatory standards and public policy goals to meet, jurisdictions can’t afford leaving grey areas in terms of what ESG actually means. The EU was the first to launch a taxonomy defining which science-based technical thresholds and activities are sustainable and which ones aren’t, and now other taxonomies are emerging in Canada, China and in the United Kingdom.

It can be expected that in 2022, the United States will take a similar path triggered by the revision of the funds name rule that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Chair Gary Gensler mentioned in his statement before the Financial Stability Oversight Council.

3. Enforcement – Market watch dogs are sharpening their vigilance tools. Most recently, the International Organization of Securities (IOSCO) endorsed the IFRS ISSB.

The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) – essentially the European SEC – included this guidance in this year’s enforcement priorities: “consistency between the information disclosed within the IFRS financial statements and the non-financial information concerning climate-related matters, consideration of climate risks, disclosure of any significant judgements and estimation of uncertainty regarding climate risks while clearly assessing materiality.”

The U.S. SEC already published a sample letter asking companies for more clarity about their disclosure practices in relation to climate risk. The letter flags inconsistencies across report types as a potential red flag: Why is a material risk as per a company’s standalone ESG/sustainability report not covered to the same extent or at all within the 10k?

More recently, Gurbir Grewal, the SEC’s Director, Division of Enforcement, said that companies “omitting ESG” can potentially be in serious trouble. It’s not about misleading or false information pertaining to ESG content. It goes one step further to address corporate silence on ESG. Companies need to prove that nothing material has been omitted, and they can do that by disclosing their process for determining material risks and opportunities.

The SEC is focused on misleading information, too. Take the Allbirds example: A shoe company that had ambitions to be the first “sustainable IPO.” It recently dropped this claim before trading this month, under pressure from the SEC and environmental critics.

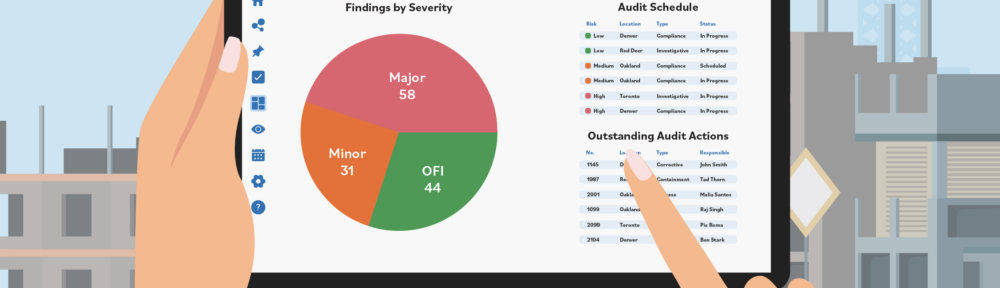

4. Technology key to strengthen internal controls – A recent report by the EFRAG Task Force on reporting risks and opportunities and linkage to the business model (PTF-RNFRO) summarizes good ESG practices. It unpacks the crucial role technology solutions play beyond ensuring data quality and comparability (on the latter, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, or CSRD, proposal adopted by the EU Commission includes the use of XBRL for data tagging).

Optimizing the use of available technologies, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP), also ensures a data-driven and auditable approach to risk identification and reporting. It enables timeliness, connectivity of ESG and financial information, stakeholder inclusiveness, strategic focus and future orientation, all while driving efficiencies and more thoughtful decision-making. In short, it’s best practice.

5. Next in line: ESG ratings – With black-box methodologies and poor correlations among their scores, ESG ratings are the next in line to receive dedicated regulation. ESMA has already asked the European Commission to take regulatory action on ESG ratings to ensure transparency, avoid conflict of interest, and better ratings for the benefit of market participants. As seen for other policies – ESG standards, taxonomy – it can be expected that other jurisdictions will follow.

So, what does this mean for companies now and in the future?

What This Means Now

Right now, ESG is a strategic imperative, that’s clear. Corporate leaders are taking ownership, recognizing the advantages gained from being more proactive and anticipating policy developments. At the core of this acceleration is one thing: a growing focus on making materiality more strategic and cohesive. Now more than ever, the process by which executives determine what’s important is center stage. As evidenced by recent SEC comments, transparency on that process matters.

We see that the practice of double materiality, which will be mandated with the EU Sustainability Standards, is maturing, as the convergence of financial and ESG information takes shape. As such, enterprise risk management processes are advancing to take more of an outside-in and forward-looking perspective.

What that means at an operational level is that the traditional barriers between ESG, finance, risk and compliance processes are dissolving. Corporate leaders are making greater investments in technology to support this, relying on data analytics to fill gaps, connect the dots and frame a more objective and dynamic governance process.

Executive Councils/Board Committees are forming to facilitate this integration at a decision-making level. They meet at minimum on a quarterly basis to pulse check on how the external landscape is evolving, using technology to monitor peer reporting, regulation, policy, media and NGO activity.

This subsequently supports what the capital markets are demanding (specifically, the SEC): better governance as reflected in more cohesive disclosures. Financial and standalone ESG/sustainability reports need to communicate a collective story about business-critical issues. This bring us back to materiality, as effective governance is rooted in an evidence-based and transparent approach to identifying, validating, and monitoring key risks and opportunities.

As Tjeerd Krumpelman, Global Head of Advisory, Reporting and Engagement of ABN AMRO said, “[having a data-driven process] improves the outcomes and also the credibility of the process to get to those outcomes.” The leaders looking ahead are those that will drive us forward.

What This Means for the Future

To have a sense of what this might look like in practice let’s draw a future scenario. It’s the year 2025.

From a reporting standards perspective, the ISSB is the baseline for reporting on ESG at global level. It goes beyond climate risk, covering natural capital and societal marginalization impacts, too. It’s been adopted by most countries around the world. Where not yet transposed in national law, IOSCO works to ensure that it’s required for listed companies. Certain jurisdictions, like the EU, have built upon the ISSB baseline to include more advanced requirements, such as double materiality.

Similarly, SEC requirements has taken shape to encompass a wider scope ESG considerations. They model the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework, focused on governance, strategy, risk management and metrics and targets.

On the ratings and rankings front, ESG rating agencies are regulated and must comply with strict conflict of interest rules and detailed disclosure requirements on their methodology. ESG scores still have differences from provider to provider, but the assumptions behind the rating approach are now publicly available. However, capital markets and investors use the ESG ratings as a baseline and prefer to build their own materiality assessment and ESG performance models based on the high quality and comparable data that companies disclose in compliance with new rules.

For business leaders, ESG data informs all decision-making processes – capital allocation, budget setting, cash flows and forecasts. C-Suite – particularly the CEO, CFO, CRO and CCO – have ESG proficiency as a baseline requirement, and relevant metrics are embedded into performance and compensation plans. “Greenwashing” is now an accounting fraud and a major legal liability risk for organizations, with market authorities having dedicated enforcement arms to keep watch.

As such, third-party assurance and legal due diligence are must-haves. Tech-enabled materiality and risk monitoring is the norm, given the dependency on combining data analytics and human intuition in order to compete in an ESG-dominated market.

Future talent is gaining ESG expertise in business schools and MBA programs, a standard component of accounting, risk management, strategy and finance courses (forward-thinking institutions like Fordham and London Business School are already doing this today).

In a scenario like this, would business finally contribute to sustainable development? That is a hard question to answer, but business would for sure be more transparent and accountable, unlocking the capital needed for the solutions to drive this. And that’s a critical step forward.

(This blog is repubished with permission from Datamaran.)