How to Prevent Workplace Hazards by Tracking Near Misses and Safety Observations

October 27, 2022

American industrial safety pioneer Herbert Heinrich long ago did the math regarding the importance of reporting and tracking of near-miss and safety observations. By his calculation, every workplace injury is preceded by up to 29 other minor injuries that may have required first aid and perhaps as many as 300 near-miss incidents where someone narrowly missed injury.

Reporting, tracking and learning from observations and near misses – those instances when someone was almost injured, machinery was nearly damaged, productivity could have been lost or a financial loss might have happened – is key to minimizing potentially catastrophic incidents. Near misses should never be ignored and safety professionals must continually track and analyze them, according to Intelex Vice President and Global Practice Leader for Health and Safety, Scott Gaddis.

Always examine your safety and injury information, identify the hazards and put programs in place to eliminate the potential for these incidents, he says. Mark Woodward, a senior safety and risk trainer at Missouri Employers Mutual, agrees, saying what an organization does after a safety observation or near miss will invariably impact the outcome of future events.

“We generally do not put enough safety emphasis on near misses in our companies,” he said during a Missouri Employees Mutual WorkSAFE podcast. “There are many companies out there that don’t even bring it up in safety meetings. There is a vast amount of information that we’re missing. Those near misses are incidents that we can learn from.”

Safety Observations and Near-Miss Reporting

Every safety practitioner wants to know when a threshold of near-loss is approached and understand high-potential workplace hazards, Gaddis says. As a safety professional in a previous role, he spent a great deal of time training workers to recognize and evaluate workplace risks. He encouraged them to raise alerts when they encountered high-risk situations.

“I wanted to know everything that workers were concerned about,” he says. “I would ask what they were most concerned about. What were the things that posed the greatest risk to them. Asking those questions opens a wide door to communication.”

Gaddis recounted an investigative safety program he introduced to 600 employees. Everyone was asked to share their top three workplace safety concerns and most offered between eight and 10, resulting in approximately 8,000 concerns raised. After detailed data analysis, approximately 80 percent were deemed truly hazardous.

“What we captured as an EHS team was about 40 percent of that 80 percent,” Gaddis says. “Near-miss and observationreporting is about severity, frequency and probability.”

Gaddis moved forward by focusing on the most severe and frequent incident first. He cited the use of utility razor knives by employees at the tissue manufacturing operation where he was safety manager. Utility knives were identified as responsible for the greatest number of injuries and close calls. So, the safety team set about critically assessing the tasks for which utility knives were used, then considered whether there might be safer alternatives to reduce their usage.

Approximately 70 utility knife tasks were initially identified and, by using alternatives, that list was pared down to two or three tasks. Through a combination of safety education and personal protection equipment, during a period of about 18 months Gaddis says utility knife injuries were virtually eliminated.

“I am sure that someone nicked themselves with a utility razor knife that I did not know about. But I do know this – there was not a recordable injury that was not reported because no one is silly enough to take that injury home with them. They want it paid for.”

He says the program was extremely successful. “I could see it in the data. (That type of injury) just went away.”

It’s how to think about a safety observation program, Gaddis says. Examine your information then use training, safety programs and better processes to remove risks. Focus first on eliminating hazards that have the greatest potential severity and risk then move on to “lower-hanging fruit.”

Incentivized Observation Reporting

Four years ago, Kloeckner Metals Corp., a distributor of steel and non-ferrous metals based in Roswell, Georgia, introduced an observation reporting program that offers cash payouts to employees. Vice President of Safety, Health, Environmental and Sustainability Rick Gruca says the close-call program was created at the behest of the company’s then new CEO, who was determined to improve the safety culture and encourage greater employee engagement.

“We felt that observation reporting would be an easy first step,” says Gruca. “We started out slowly by introducing a campaign for the fourth quarter in 2018 and saw great results. So, we decided to continue the following year. In 2018 (prior to the program), we were averaging 15 OSHA recordable injuries (including) seven lost-time injuries per month. In Q4, that went down to five per month (including) one lost-time injury.

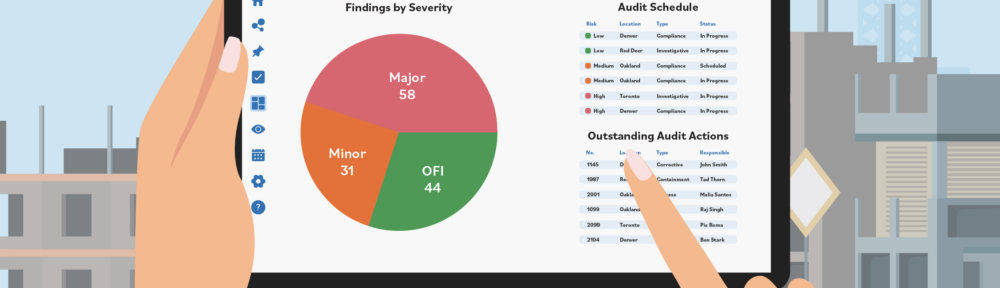

The program works by having employees fill out “cards” customized for each Kloeckner branch. Requested reporting information includes a description of the observation, the date it happened, an assessment of the potential severity and any corrective action taken. Submissions are reviewed by supervisors, who then enter the information into the company’s Intelex EHS management system that generates and distributes weekly close-call reports across the organization.

“We believed incentives would be money well spent if it resulted in employees becoming more proactive in identifying unsafe conditions and at-risk behavior,” Gruca says. “I have never been a fan of safety incentives, personally, but we really needed to change the culture. Once the (initial pilot) campaign was over it became very clear, based on injury rates, that there was correlation between the program and (decreased) injuries.”

Kloeckner leadership assures its employees there will be no repercussions for those who report near-miss incidents. The observation reporting program continues, and the improvement in the safety performance has been dramatic. The company’s most recent metrics show OSHA recordables are down 52 percent since the program began and lost-time injuries are 75 percent lower.

Removing Observation Reporting Risk

Like the proverbial tree falling in a forest that you might never hear, a single individual might be the only one to witness a near miss or close call and a company won’t likely hear about it.

“The biggest thing we need to focus on in near-miss reporting is open and honest communication,” Woodward says. “In the world of safety and workers’ compensation, we associate incident reporting with disciplinary action, corrective action, post incident drug and alcohol testing and filling out forms. But what is of much more value is the fact that an employee openly and honestly came to your office and said, ‘listen, I did something today, it’s been bothering me and I wanted you to know about it because I don’t want it happening to someone else.’”

Safety observation programs should be voluntary, confidential and, as previously mentioned, assure that punitive action will not be taken against employees demonstrating non-compliant behavior or those who report concerns. Program objectives should discover unknown safety risks and eliminate hazards through preventative safety action.

Managers must be educators and speak with their employees more frequently and openly about near misses, Woodward says. They should define near misses and close calls and how important it is to report them in order to maintain a safe working environment.

Response to Near Miss Reports Is Vital

It’s one thing to talk the talk. Perhaps the worst thing any organization can do is to hear but not listen. When employees raise concerns or report near misses and safety observations, company leadership is obliged to quickly respond. It must follow up with action or explain why there won’t be follow up, Gaddis says.

“People come to work to partner with you,” he says. “If they feel valued, they’ll want to participate. What they really want is to be a business partner. They want to be a part of a plan that makes their lives easier and enriches their pockets. “Once they recognize that you will do what you say then they’re much more willing to participate, which is necessary to achieve lofty safety goals. Unless you truly partner with people, you’re not going to sustain world-class safety performance for very long. You can get there – you can drive people that way, but you won’t keep them there if you don’t act.”

Take workplace safety to the next level by proactively tracking and managing near-miss incidents. Watch the Intelex Near Miss Reporting software demo to see how it empowers you to prevent hazards before they happen.