It’s Time to End the Blame Game and Start a Just Safety Culture

December 23, 2021

It’s often said that accidents will happen, but in many workplaces there’s a tendency to blame someone for the mishap. It’s the kind of thinking that harms efforts to keep workers safe.

So says health and safety professional Rod Courtney who shared his views on how to create a “just” safety culture during a keynote speech at the recent EHS Today Safety Leadership Conference. Human errors in the workplace are normal and even the best people make mistakes on the job.

“Blaming those who make mistakes fixes nothing. We need to stop blaming people,” Courtney says. “It’s human nature to find fault. It’s human nature to find out who did it, someone to blame for this. But we need to stop it.”

Organizations must move away from the idea of “fixing” workers who do unsafe things and instead build a just safety culture where trust in workers is established, people feel safe to communicate their concerns and observations, and are apt do the right things regardless of who is watching.

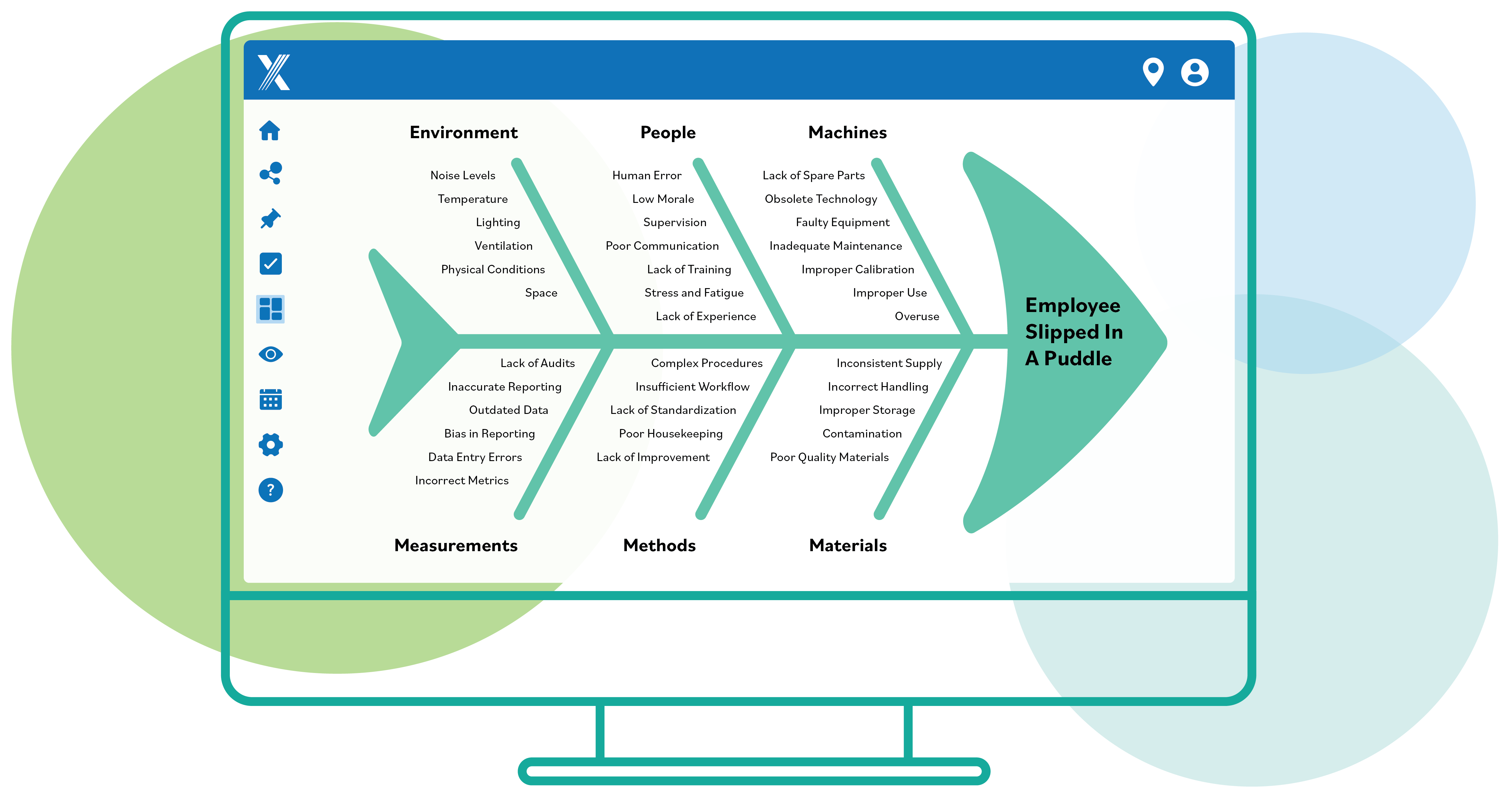

Courtney explains that when workplace incidents occur, companies typically conduct a root-cause analysis that invariably seeks to point an accusing finger at an employee who may have violated a rule or wasn’t paying attention. “It was the employees fault. We do this over and over,” he says.

Once a culprit is found the typical next step is to counsel and discipline the offender. But that can lead to loss of trust and often discourages other workers from communicating when incidents happen, fearing similar reprisal. Safety communication then stops and management loses insight into jobsite conditions, which creates latent organizational weaknesses and flawed defenses to mitigate incidents. In this scenario ultimately more human errors will happen.

“Step Number 1 starts right here. Stop counseling, disciplining, calling out people for errors,” Courtney says, explaining that people make errors all day long no matter how much you train them. Disciplining and calling out individuals for their mistakes is counterproductive and typically reduces safety awareness.

A just safety culture is one that continually encourages worker communication and creates a safe environment for people to raise concerns regarding safety, quality of life and dignity and respect on the job. Even in a just safety culture mistakes will continue to happen, but you want workers to report these and for management to be aware of them. Courtney says that, in a just safety culture, everyone wants to be accountable because repercussions only happen when someone is culpable and did something they knew was wrong but went ahead and did it anyway.

When an accident occurs, there are two choices – get better or get even. “You can blame and punish, or you can learn and improve, but you cannot do both,” Courtney says.

Organizations also need to be aware of near-miss incidents or close calls where an unsafe situation had the potential to cause an accident, but was recognized before any human injury, environmental or equipment damage, or interruption to a normal operation happened. But companies too often see a near miss as a bad thing and these often go unreported for fear of reprisal. Courtney considered the question of how an organization might respond if a near-miss incident was reported every day.

“Would they lose their minds? Would they freak out? A lot of times they would,” Courtney said, adding that, “Near misses are happening, whether they are reported to you or not. Why not get them reported? Why not put them into a system and track them?”

Tracking near-miss incidents help organizations learn and better understand the risks that exist. He believes a near-miss should be look upon as a positive thing. Courtney explained that management at his company actually rewards people with gift cards and other tributes for reporting near misses.

“We went from (reporting) one near miss a month to sometimes 10 in a week. And that’s still not all of them,” he said, explaining that entering near-miss data into a tracking system helps an organization recognize and minimize hazards, supports efforts to be predictive about incidents and improves safety. Injuries drop and ultimately near misses are reduced.

“If you can get people to report this stuff you can literally see into the future,” Courtney says. “But we have to establish trust and respect.”

For more about Safety Culture, read our blog “Lucky #7: Tips to Develop a Laser-Focused Safety Vision for 2022” and the insight report, “Building a World-Class Safety Culture.”