Energy-Based Safety: A New Approach to Preventing Serious Injuries and Fatalities

December 2, 2025

5 minute read

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: while Total Recordable Injury Rates have dramatically reduced over the last 20 to 30 years, the fatality rate has stayed flat.

What this tells us is that we’ve gotten good at preventing relatively minor injuries, but we have not been successful at preventing workplace deaths.

Why? Because, as recent research has shown, the things that hurt people aren’t the same as the things that kill people.

What is energy-based safety?

Energy-based safety is built on a simple principle: All injuries result from contact between a person and an energy source. Furthermore, the larger the energy source, the more severe the injury.

The breakthrough insight is that high-energy hazards, those exceeding 1,500 joules of physical energy, are most likely to cause serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs).

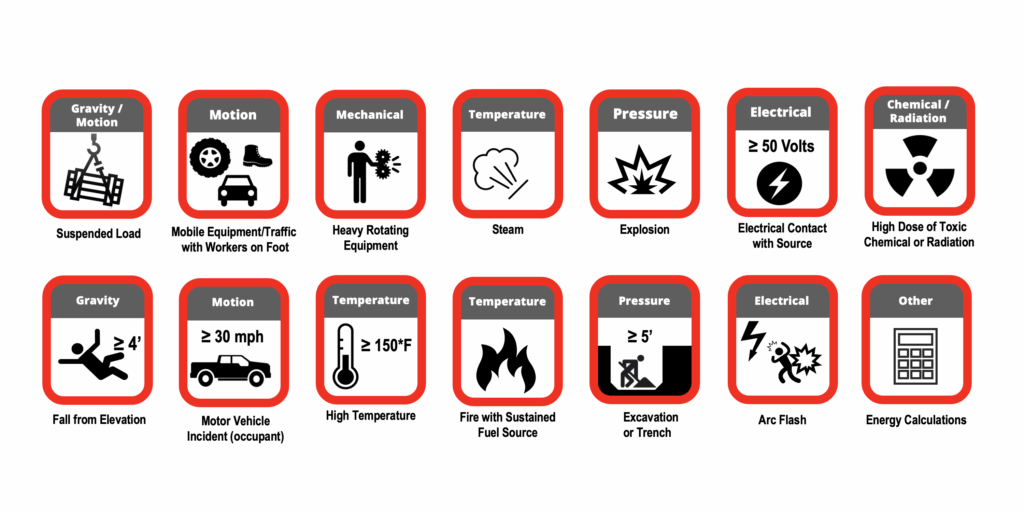

To simplify this high-energy hazard concept for in-field assessments, the Edison Electric Institute developed 13 high-energy hazard icons. According to the analyzed dataset, the icons represent the 13 high-energy hazards that account for 85% of all SIFs.

That’s the 80/20 rule at work.

Why high-energy hazards are often missed

Most in-field monitoring processes, such as observation programs, hazard ID programs, and behavior-based safety programs, end up capturing what’s easy to see: missing PPE, housekeeping issues, etc.

These “low-hanging fruit” observations matter, but they don’t address many of the critical high-energy hazards and energy sources that are most likely to result in SIFs or pSIFs on the job.

Why some hazards are easily identified and others are not

Research is beginning to show why some hazards are easily identified and others are not. It all comes down to cognitive load. Different types of energy require different levels of cognitive effort to identify the hazard.

- Hazards that are easily identified (e.g., gravity or motion) are readily apparent, making them less taxing for our brains to detect.

- Hazards that are most often missed (e.g., mechanical, pressure, chemical, or radiation) are processed by a different part of the brain, requiring more analysis and decision-making.

This is one of the reasons why people naturally focus on what’s easy to process.

This shows that unidentified critical hazards in work tasks cannot be fully blamed on complacency. Our biology causes cognitive shortcuts and a focus on the “low-hanging fruit.”

This is where energy-based safety tools help by giving managers, supervisors, and frontline employees structured guidance to improve hazard identification, especially for high-energy hazards in their work tasks.

The three core tools to improve hazard identification

Energy-based safety provides three practical tools:

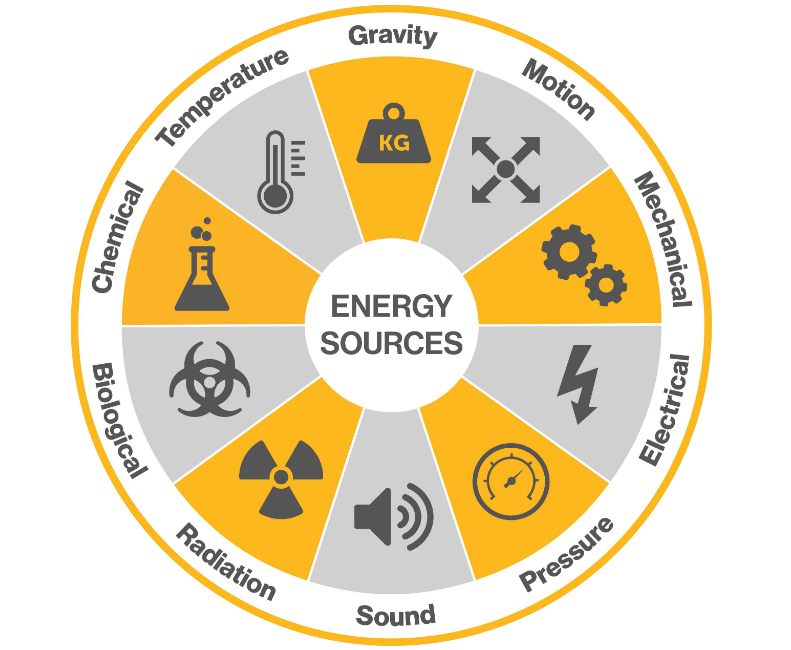

1. The energy wheel

The energy wheel organizes hazards into 10 energy categories (gravity, motion, mechanical, electrical, sound, pressure, temperature, chemical, radiation, biological).

Field experiments have shown that when used as a guidance tool during pre-job briefs, it improves hazard recognition by approximately 30% on average.

2. High energy control assessments

High energy control assessments (HECA) give companies a quantitative assessment of safety capacity in their job tasks by identifying high-energy hazards and measuring the percentage that have Direct Controls. These safeguards target the energy, mitigate or eliminate it, and work even if someone makes a mistake.

HECA = Success / (Success + Exposure)

Success: Total number of high-energy hazards with a corresponding Direct Control

Exposure: Total number of high-energy hazards without a corresponding Direct Control

This method focuses on monitoring known hazards that cause SIFs and shifts measurement from counting injuries and observations to measuring the presence of adequate controls for critical hazards.

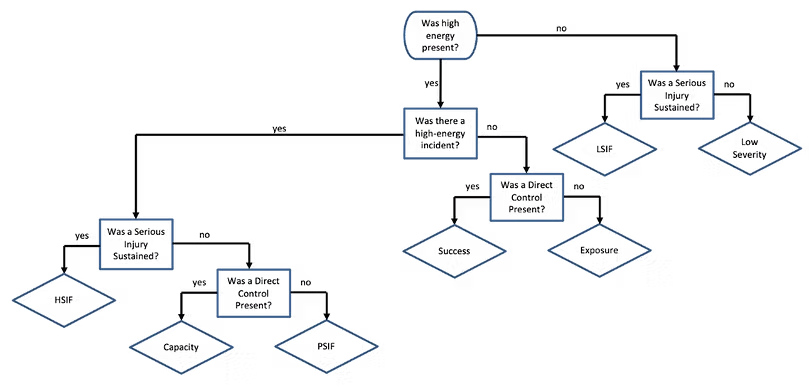

3. Safety classification and learning (SCL) model

Developed by the Edison Electric Institute, SCL uses simple yes/no questions to consistently classify incidents, near-misses, and observations into seven categories.

This creates a common framework that connects lagging and leading indicators, enabling you to apply energy-based safety principles to standardize event categorization and prioritize learning from SIFs and potential SIFs.

How this transforms your EHS management system

Energy-based safety doesn’t replace your existing processes. The tools can be embedded in or added on top of current processes:

- Using the energy wheel and high-energy icons in Pre-Job Briefs and JSAs help crews identify more hazards and more critical high-energy hazards associated with the tasks.

- High Energy Control Assessments generate actionable insights and real time metrics focused on high-energy hazards instead of the typical “low-hanging fruit”.

- Event investigations are prioritized for the SIFs and p-SIFs categorized through the SCL model framework.

- Safety investments get directed where they’ll prevent serious injuries and fatalities, not just recordables.

Using these energy-based safety tools helps companies improve hazard identification and collect more actionable data targeted at hazards most likely to cause SIFs. This leads to more strategic resource allocation in your hazard mitigation processes.

Ready to move beyond the fatality plateau?

Intelex has incorporated similar energy safety principles into our platform with our energy based observation application.

Contact us to see how Intelex can help your organization systematically identify and control the hazards that lead to serious injuries and fatalities.

References

Oguz Erkal, E.D. & Hallowell, M.R. (2023, May). Moving beyond TRIR: Measuring and monitoring safety performance with high-energy control assessments. Professional Safety, 68(5), 26-35.

Hallowell, M.R. (2021, December). The art & science of energy-based hazard recognition. Professional Safety, 66(12), 27-33.