Human Error: The Myth of Blaming Workers for Safety Failures

December 13, 2022

Scapegoating workers and accepting the limitations of human judgement does nothing to reduce injury and fatality rates or to improve the efficiency of the EHS management system.

When we say that human error was responsible for an incident, it’s tempting to be comforted by the idea that one person’s poor judgement was to blame. If that person was doing something they shouldn’t have been doing, that seems to be a fairly obvious root cause that couldn’t be anticipated and doesn’t reflect the overall integrity of the management system, leadership or workplace. “Humans will always make mistakes,” we might tell ourselves, “and you can’t make a system foolproof when humans are involved.”

Yet scapegoating workers and accepting the limitations of human judgement does nothing to reduce injury and fatality rates or to improve the efficiency of the EHS management system. People operate within the constraints provided by the culture and management system of the organization. When workers do something unsafe, the decision they made to do so was the result of uncontrolled variation within the work system of the organization.

Safety Failures and Death on a Construction Worksite

In August 2019, the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure was constructing a bridge near Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada. Towards the end of the day, two workers, James Martin and Eric Turner, installed a temporary wooden barricade on the side of the bridge, which is required for all workplaces higher than 1.2 meters. Although they would normally secure the barricade using bolts, they instead used zip ties and wire, intending to complete the work by installing the bolts the next day.

The following morning, the team moved on to other tasks and forgot about the temporary fasteners on the barricade. During the 1:15 pm break, Martin leaned back against the rail to relax and broke through, falling 3.35 meters onto the rocks below. He passed away later that day in hospital.

The following year, the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure was fined $125,000 for failing to provide safe guardrails and for not filling out a risk assessment form that was required for that and similar projects.

It would be easy to attribute this tragedy to “human error,” but would that really provide a satisfactory explanation for what happened?

Do Workers Really Choose to Make Errors?

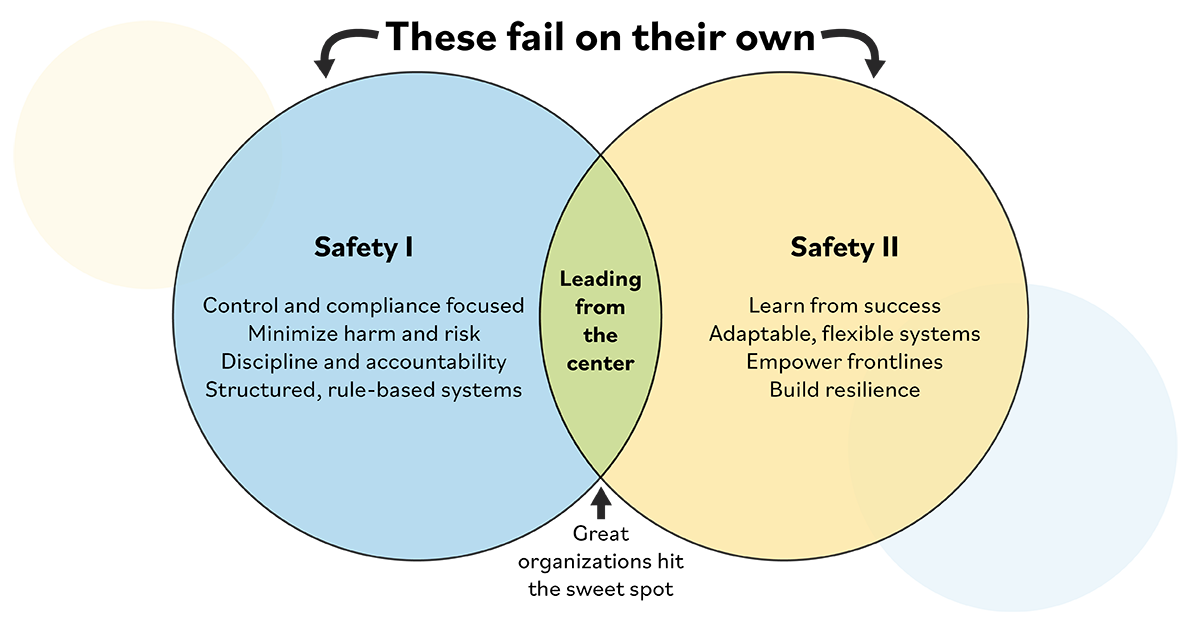

According to safety expert Scott Gaddis, efforts to improve safety in the workplace are often hobbled by the focus on carelessness as an unqualified explanation of accidents instead of an understanding of the multiplicity and variables of the complex organizational system. In other words, human error is not unto itself a straightforward root cause. Instead, it is a contributing factor that is facilitated by uncontrolled, loss-producing variability throughout the EHS system.

Gaddis identifies three types of errors that result from system variability:

- Latent errors: These are errors in system design, management decisions, organization, training or maintenance that facilitate operator errors. These errors can remain dormant in the system for long periods of time before they aggregate into an incident.

- Armed errors: These are errors that are primed to occur but haven’t yet done so.

- Active errors: These are errors that have occurred, the consequences of which have been felt immediately by workers on the front line.

In the Woodstock example, the system variability that allowed the workers to install the barrier with insufficient fasteners was a latent error. Once the barrier was erected with zip ties, it became an armed error, and it became an active error as soon as the incident occurred.

According to Gaddis, 90 percent of all incidents are the result of unsafe acts committed by workers. Most leaders might conclude that the solution is to lay the blame at the feet of the workers and improve the EHS management system by enforcing training. However, as Gaddis points out, humans are the least predicable element in any EHS system, which means there will always be the opportunity for variability regardless of how much training the workers receive. Deming’s 85/15 rule—part of his 14 Points for Management—tells us that while 15 percent of a company’s problems are caused by the workers, the management system is responsible for 85 percent, which means that the vast majority of incidents occur because the management system nurtures the variability that allows them to happen.

How to Reduce Safety Failures Effectively

Effectively reducing safety failures requires addressing the system variability that allows workers to choose unsafe approaches to their tasks. Gaddis cites the hierarchy of controls and Inherently Safer Design (ISD) as potential ways of doing this.

The hierarchy of controls implements controls with varying degrees of effectiveness to minimize hazards within the work system. Table 1 shows the hierarchy of controls, with the controls listed in the order of most effective to least effective.

| Control | Description |

|---|---|

| Elimination | Elimination involves removing the hazard at the source by changing the work process. |

| Substitution | Substitution involves finding safer alternatives to hazardous elements. |

| Engineering | Engineering involves modifying equipment or processes to prevent workers from coming into contact with them. |

| Administrative | Administration involves establishing work practices that reduce exposure to hazards. This can include training and job rotation. |

| PPE | PPE involves equipment, such as gloves and hard hats, to minimize exposure to hazards. |

Inherently Safe Design assumes that safety should be designed into the lifecycle of a process, not simply controlled. Key areas are shown in Table 2.

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Minimize | Reduce hazardous material. |

| Substitute | Replace hazardous material with safer material. |

| Moderate | Reduce the potency of hazardous materials. |

| Simplify | Eliminate hazards during the design process. |

The work system has four key areas, all of which are interdependent on one another and must be nurtured to create an effective safety culture. Change in one can have a knock-on effect throughout the system, which is the variability that frequently leads to accidents. Table 3 shows the critical areas and the potential variables in each.

| Area | Potential Variables |

|---|---|

| Work Environment | – Equipment – Tools – Procedures – Purchasing – Work Design – Engineering |

| Behavior | – Mentoring – Leading – Coaching – Following – Accountability – Expectation |

| Leadership | – Supporting – Communicating – Disciplining – Recognizing – Recognizing – Evaluating – Analyzing – Creating Value |

| People | – Knowledge – Skill – Training – Intelligence – Stress – Motivation – Hiring |

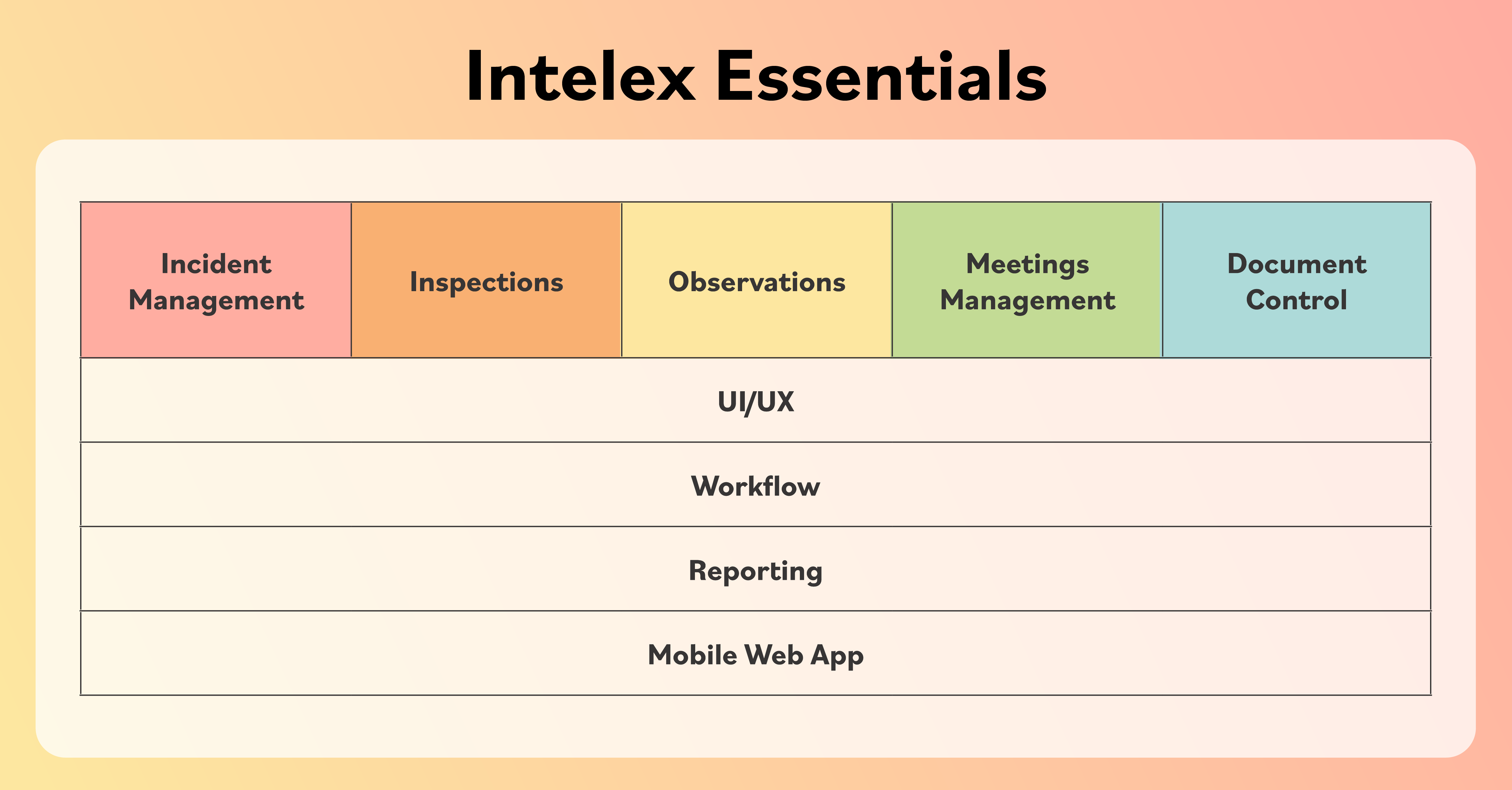

Putting these approaches into action requires analyzing data from past incidents, near misses, inspections and maintenance logs with EHS software, which will facilitate benchmarking with similar industries to better understand latent errors that might be residing in the system, as well as the severity, frequency and probability of recurring errors.

Once the data has been compiled and analyzed, it will be easier to diagnose system errors, including behavior and leadership factors, to determine alternatives and potential solutions. After gaining leadership endorsement for solutions, organizations can implement changes, monitor for compliance and revise as needed.

Conclusion

People often take false comfort in discovering that “human error” is the root cause of an incident. “It was the worker’s fault,” they think. “The system is fine. We’ll do better training and it won’t happen again.” As we’ve seen, however, human error is not a root cause unto itself, but is instead a symptom of deeper systemic problems that foster variability and allow workers to choose unsafe practices that lead to incidents. By understanding the role of variability, designing safe practices and controlling the hazards that remain, organizations can enculturate workers to make safe choices that prevent incidents.

Ready to turn safety data into actionable insights and drive culture change? Watch our on-demand webinar, ‘Changing Culture With Data,’ and learn simple strategies to transform your EHS data into powerful tools for improvement.